How to release fraud rules safely

This is the second post in our 2026 Fraud Ops series, where we explore the practices that help fraud teams operate with greater accuracy, confidence, and speed. If you missed the first post, catch up here to learn 5 creative ways that fraud teams can use AI right now.

Releasing new fraud prevention rules can be a double-edged sword.

Any fraud fighter that ever deployed a new rule knows that feeling: waiting for the first hits to show up on screen, while dreading the possibility that a small mistake might tank business performance.

As much as we need fraud rules to combat fraud, the hard truth is that any change in the system (big or small) presents an opportunity to introduce a bug.

Every fraud leader I know, myself included, has their share of horror stories to tell. But this doesn’t have to be the case. With a proper validation process, your team can reduce the risk of releasing new rules.

Here’s how to build a safe, reliable fraud rule-release process that your team can implement with confidence.

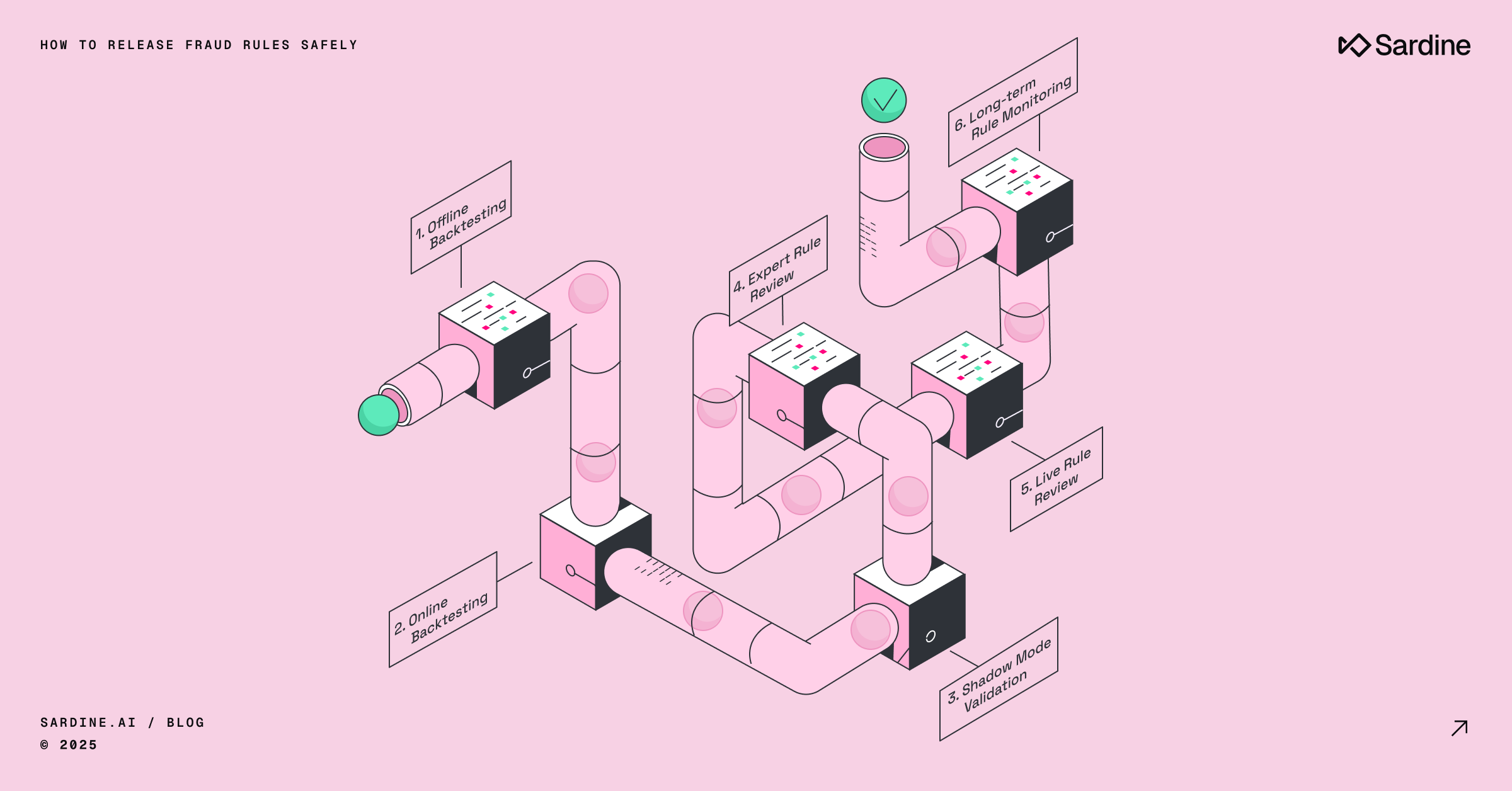

How to structure your fraud rules release process

A fraud rules release process is designed to ensure that new rules hit the right population when they go live.

Whether you’re looking to flag suspicious behavior for review or outright block these events, the goal is accuracy. When a rule is improperly released, you can run into two issues:

- The rule fails to hit the bad population and generates false positives

- The rule impacts a disproportionate number of legitimate users

While the former can be difficult to identify, the latter carries far greater operational and customer risk. A well-designed rule release process can virtually eliminate both of these scenarios entirely.

In my experience, the safest way to ship fraud rules is to treat release as a process, not an event. I recommend a six-step process, outlined in the table below.

Step 1 - Offline backtesting

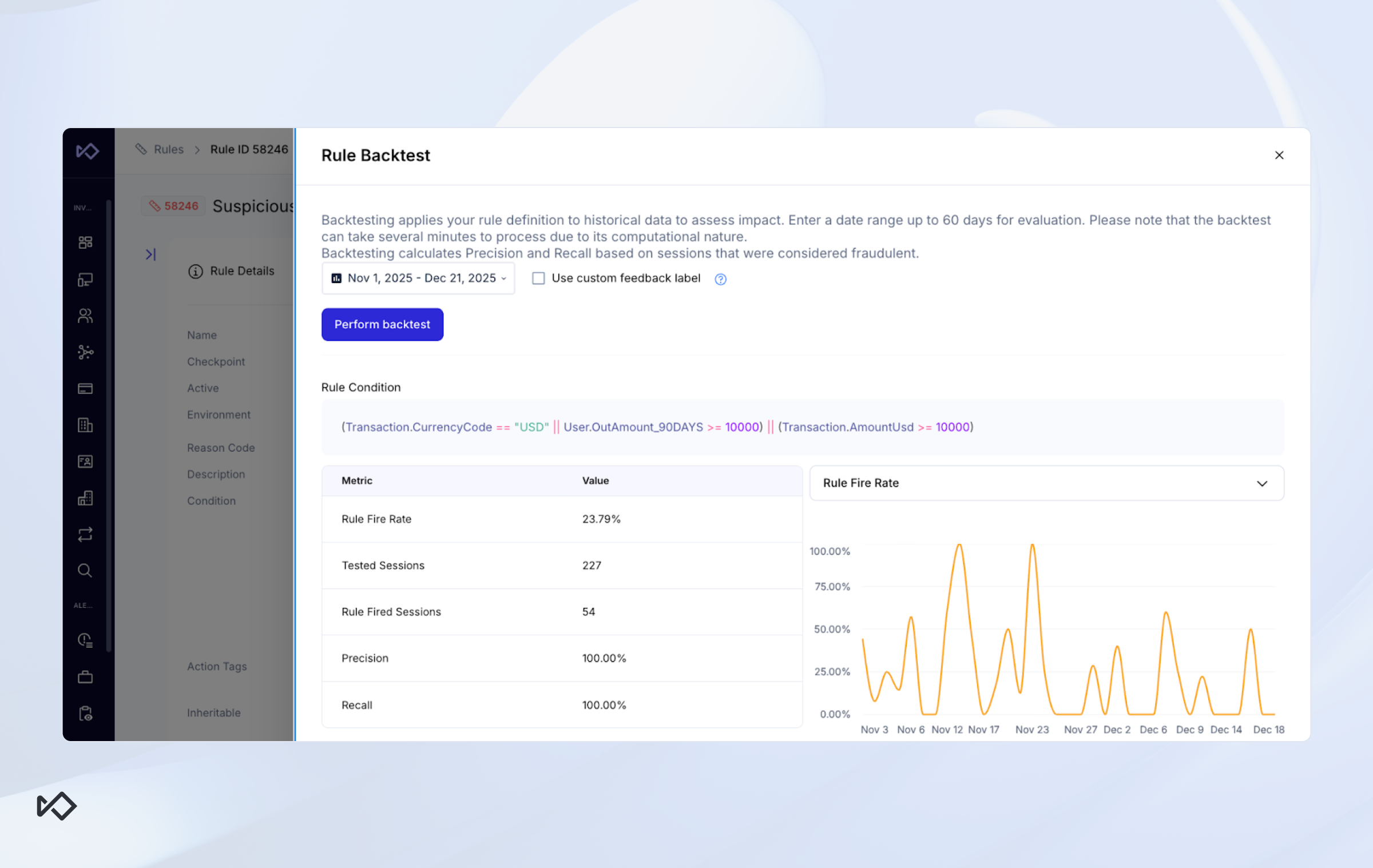

A new rule starts with a mini research project, where the fraud fighter iterates on the pattern they wish to capture over historical data. This work typically happens in your in-house acceptable quality level (AQL) data warehouse, where the goal is to measure how the rule would have performed against key metrics if it had been live historically. In each iteration, the analyst improves the overall performance of their logic until they are satisfied with it.

Naturally, this begs the question of what “satisfied” means in this context. The last thing you want is a situation where each team member has their own quality standard. For that reason, it’s imperative that fraud teams have a predefined policy that dictates what success criteria new rules need to uphold to be considered “production worthy”.

These success criteria, expressed as metric thresholds, vary not only across organizations but also based on the rule’s objective.

A rule that automatically blocks events needs to be more accurate than a rule that flags cases for manual review.

A rule that overwrites blocks to avoid false positives would be optimized around different metrics than a “regular” fraud reduction rule.

Regardless of the goal, the success criteria should support a holistic view of the rule’s impact.

Step 2 - Online backtesting

Once the fraud fighter is satisfied with their SQL logic, they now need to “translate” its syntax into the confines of their rule engine. Sometimes it’s a simple exercise (i.e., amount > $100 AND risk_score > 80), but on other occasions this can get pretty hairy.

One common challenge is that features available in the rule engine often require awkward or hacky regex logic to replicate in the local data warehouse.

Another is that features like velocity counters are hard to reproduce, especially point-in-time, with SQL.

No matter the reason, the mere fact that you’re transplanting code from one system to another is a major vulnerability. To validate that the rule behaves as expected, like the SQL query did, you also want to backtest the rule within the rule engine itself. Ideally, you’d run it on the same population and timeframe as your SQL backtest population. Then all you need to do is to compare the lists of tagged events and make sure they’re the same on both versions.

Step 3 - Expert review

Implementing the “four-eyes” principle for system changes may already be a formal requirement in your organization. Even if it isn’t, introducing this checkpoint is strongly recommended: fraud rules can wreak havoc on production systems, and in most cases, failures stem from simple human error.

As a final safeguard before going live, ensure that a seasoned specialist reviews and approves the new rule. If your team has similar levels of experience, a structured peer review can still significantly reduce the risk of errors.

The reviewer’s role is to make sure that best practices are upheld, including:

- Backtesting shows good performance

- Documentation matches the syntax

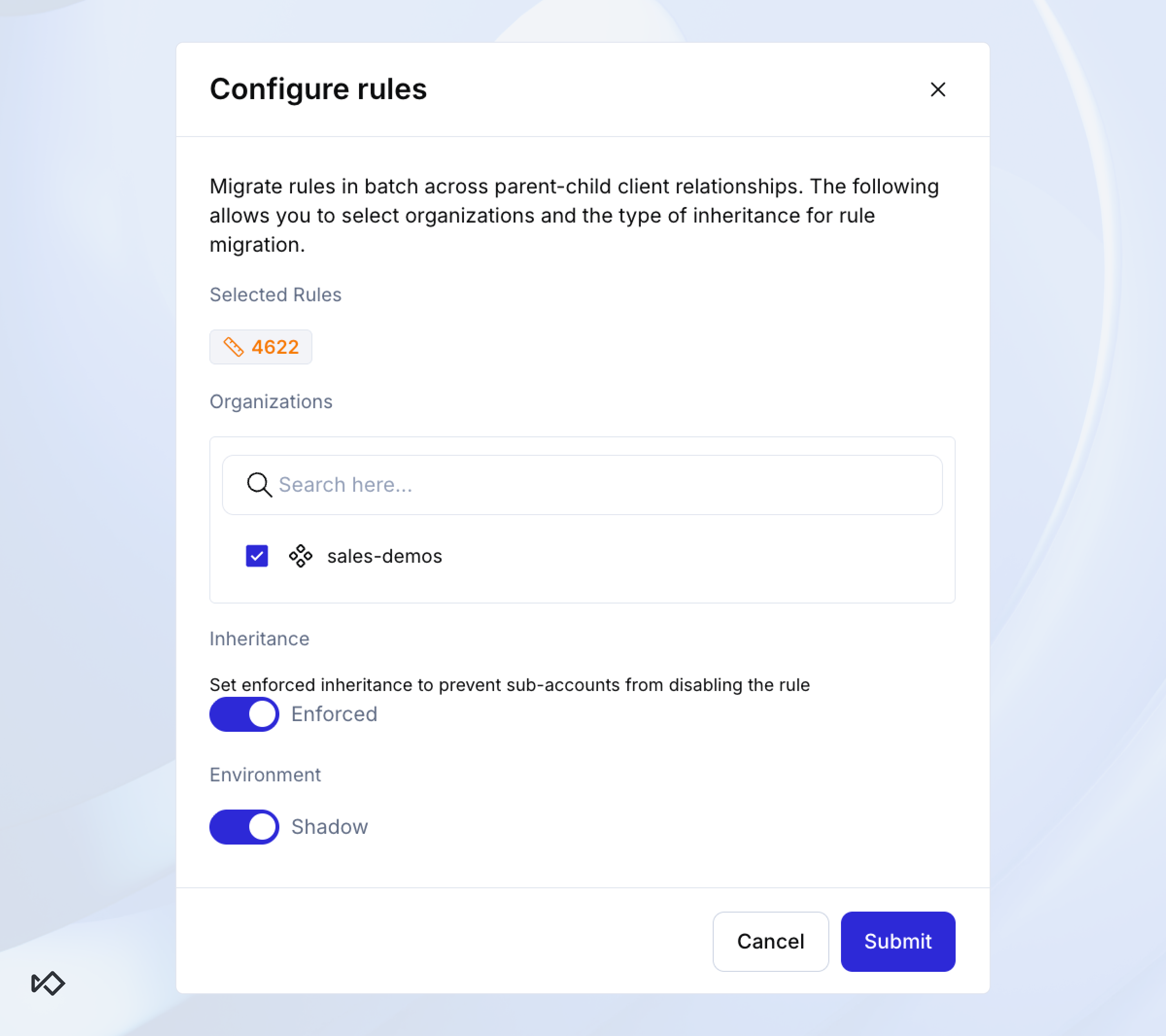

- The rule is properly tagged and configured in “shadow mode”

A reviewer can also sanity-check the rule outside the bounds of the dataset, such as were peak seasons taken into account? Did we exclude a new product line that wasn’t in the dataset?

Once the review has concluded successfully, the reviewer can activate the rule and release it to the live production environment.

Step 4 - Live validation in shadow mode

As mentioned in the previous step, new rules should ideally be released in “shadow mode,” where they tag events they would have acted on without actually enforcing any action. This makes it possible to monitor performance and confirm the rule behaves as intended, without taking on unnecessary risk.

The goal of this step is to rule out the worst-case scenario described earlier: a rule that unintentionally affects so many legitimate users that it immediately triggers a business-wide incident. This happens more often than you might suspect, sometimes due to something as small as flipping “score > 90” to “score < 90,” which can suddenly block 80% of traffic.

Monitoring the volume of events a rule would hit while it’s in shadow mode allows you to safely detect these issues early. As a general rule of thumb, new rules should remain in shadow mode for at least a week to confirm that live behavior aligns with the historical performance that justified releasing the rule in the first place.

In case you skipped “shadow mode” due to urgency (or the lack of it), you should still execute this step while monitoring live results. Keep a close eye on the rule for the first 24 hours, especially during the first hour, to rule out catastrophic malfunctions.

Step 5 - Live review in production

In this step, your goal is to avoid another unwanted scenario: the rule doesn’t manage to catch the fraud pattern you’ve designed it for and is mainly blocking false positives. However, this is trickier to accomplish than it seems.

If an event is blocked, how do you know it was actually fraudulent? Without chargebacks or customer complaints, there’s no direct way to measure blocked fraud or false positives in your dashboards. For all you know, the rule could be blocking the expected volume of events, but they also may be false positives.

The best way to get a “quick and dirty” validation is to manually review a sample of the rule hits and compare the results with your backtests. If you expect a significant part of the population to be fraud, you don’t need to review too many cases. Usually, 50-100 manually labeled cases offer a good indication of whether the rule is performing as expected.

Keep in mind that if this review is used purely for temporary labeling rather than enforcement, case-level accuracy is less critical. What matters most is gaining a high-level view on the otherwise hidden metrics you’re trying to uncover.

Once you’ve successfully completed this step, you can safely conclude that your rule is safe and ready to be fully live. It’s time to turn off “shadow mode.”

Step 6 - Long-term monitoring

Knowing your rule behaves as expected at time of release is great news, but that doesn’t mean it’ll stay like this forever. Every fraud fighter knows that rules, like fruit, start to rot the minute you ship them.

Eventually, fraudsters will evolve and change their patterns, new false positive patterns will emerge, and your rule’s performance will deteriorate.

The final piece is putting rule alerts in place to warn you when this starts to happen.

Consider these two alert cases:

- The issue: The rule should goes haywire and starts blocking large swaths of your population.

- The fix: Implement alerts that monitor the rule’s hits and trigger if a predetermined threshold has been reached. To avoid too many false positives, set the thresholds generously.

- The issue: The rule’s accuracy is slowly deteriorating and is more complex to alert on.

- The fix: The most accurate way to measure the false positive rate of a live rule is with a control group that overrides the block for a small, random population. Note that this approach is unlikely to be effective for most rules, particularly those that aren’t designed to decline large volumes of events each day.

While there are different ways to get an approximation of accuracy in an automated manner, most teams would find them too complex to implement. For that reason, it’s best to start with a periodic review of live rules every six to 12 months.

Congratulations! Once your alerts are set up, you can consider your rule fully released.

Assess yourself: How safe is your fraud rule deployment process?

As we noted, the process above represents the full set of best practices. Realistically, though, your team might miss many of the pieces and the task to implement the process in full might be daunting. That’s ok, it’s not a zero-sum game.

Here are the milestones you want to slowly hit while you work your way through it:

.png)

Releasing fraud rules doesn’t have to be a leap of faith. With a structured validation and monitoring process, teams can ship faster, reduce risk, and maintain high system performance, even as fraud continues to evolve.

Frequently asked questions

[[faq-section-below]]

- What success criteria should we use to evaluate a rule?

A new fraud rule should reflect the pre-agreed understanding of the trade-off the business is willing to make between stopping fraud and creating new false positives. Whatever metrics you use, make sure they reflect this tension. A good rule of thumb is to use your overall fraud system performance as the baseline to beat for a new rule to be released. For example, if the sum of all of your rules and models translates to 80% precision and 2% recall, both of these metrics should be improved in order to approve a new rule. In that way your rules are guaranteed to have an overall positive impact. - What’s a “safety-net rule,” and why should fraud teams use them?

Safety-net rules aren’t designed to stop everyday fraud patterns, they’re designed to protect you against catastrophic, worst-case scenarios that could threaten the business. These rules typically use high-threshold velocity counters or broad limits to catch massive, unlikely bursts of fraud that your regular rules might miss. They’re meant to rarely if ever fire, but if they do, they prevent extreme losses and give your team time to react without a crisis. Having them in place can reduce stress around rare but high-impact fraud events and ensure you’re prepared for exceptional spikes in risk. - Should fraud rules ever be designed around limiting exposure rather than blocking threats outright?

Yes, limiting exposure (e.g., capping transaction sizes or restricting new accounts) can be a strategic tool, not just a last-resort control. Limits don’t stop fraud completely, but they force fraudsters to scale their operations to reach economic targets. Each additional attempt presents more signals and patterns you can detect, turning limits into detection mechanisms rather than just loss caps. - Why can a rule look “good” in testing but still tank performance live?

A rule can appear effective in isolation, high precision on paper, or strong historical backtest metrics, yet still perform poorly in production because evaluation metrics alone don’t capture real-world impact. Teams often rely on terms like recall or false positive rate, but these don’t measure incremental benefit, such as how much extra fraud the rule catches above and beyond the existing system or whether it introduces hidden costs to the business. The best way to validate a rule’s performance is to look at precision in context, incremental impact on the overall system, and real-world business metrics (e.g., value saved vs. conversions disrupted). This systemic view helps you spot when rules that “look great” on paper actually add noise or degrade operations in practice. - Why is offline backtesting not enough?

Offline backtesting shows how a rule would have performed using historical data, but it doesn’t confirm how it behaves in your live system. Online backtesting and shadow mode are necessary so the rule functions as intended when deployed.

%20(1).png)