The 3 failure modes of AI agents in financial crime (and how to avoid them)

Financial crime teams are at a breaking point.

Not because fraud is new or because money laundering is suddenly harder to detect. But because the scale of financial crime is now fundamentally mismatched with the way most institutions are staffed and operated.

A typical financial services company has an enormous percentage of its workforce tied up in investigation-heavy workflows: fraud operations, transaction monitoring, sanctions review, onboarding compliance, disputes, and customer support.

Fraud isn’t just increasing, it’s accelerating faster than any human team can respond.

Scammers are using AI. Deepfakes are getting cheaper and more convincing. Attack cycles are shrinking.

And yet inside most institutions, the day-to-day reality looks the same: alert queues dominated by false positives, customers locked out for no clear reason, legitimate businesses stuck in review limbo.

Just two years ago, the only lever banks and fintechs could pull to address it was to throw even more warm bodies at it.

But it’s 2026, and the industry is doing what it always does when manual work becomes unscalable: it’s turning to automation. Only this time, it actually has the means to do so with Agentic AI.

Specifically, AI systems that can gather evidence, interpret context, produce investigation-ready conclusions, and in some cases, even take action autonomously.

And yet, despite all the excitement, most early deployments of AI agents in financial crime fail.

Not because the models are weak, but because how they are deployed is wrong.

How so?

In regulated environments, an agent that produces confident narratives without guardrails doesn’t reduce risk, it creates a new one.

And risk teams, surprisingly, don’t like risk.

These teams quickly realize they end up spending their time on validating, correcting, and hand-holding AI agents.

They aren’t more efficient. They aren’t spending their time on more important tasks. Frustration builds, and the project gets bogged down, or in the worst case scenario - it gets completely sidelined.

But if you deploy it correctly?

When we A/B tested on Sardine’s own on-ramp platform, we found that flows supported by AI agents didn’t just reduce labor. They also showed 49% faster time-to-revenue. That’s a quantifiable impact on business growth, not just efficiency savings.

Why fincrime teams fail with Agentic AI

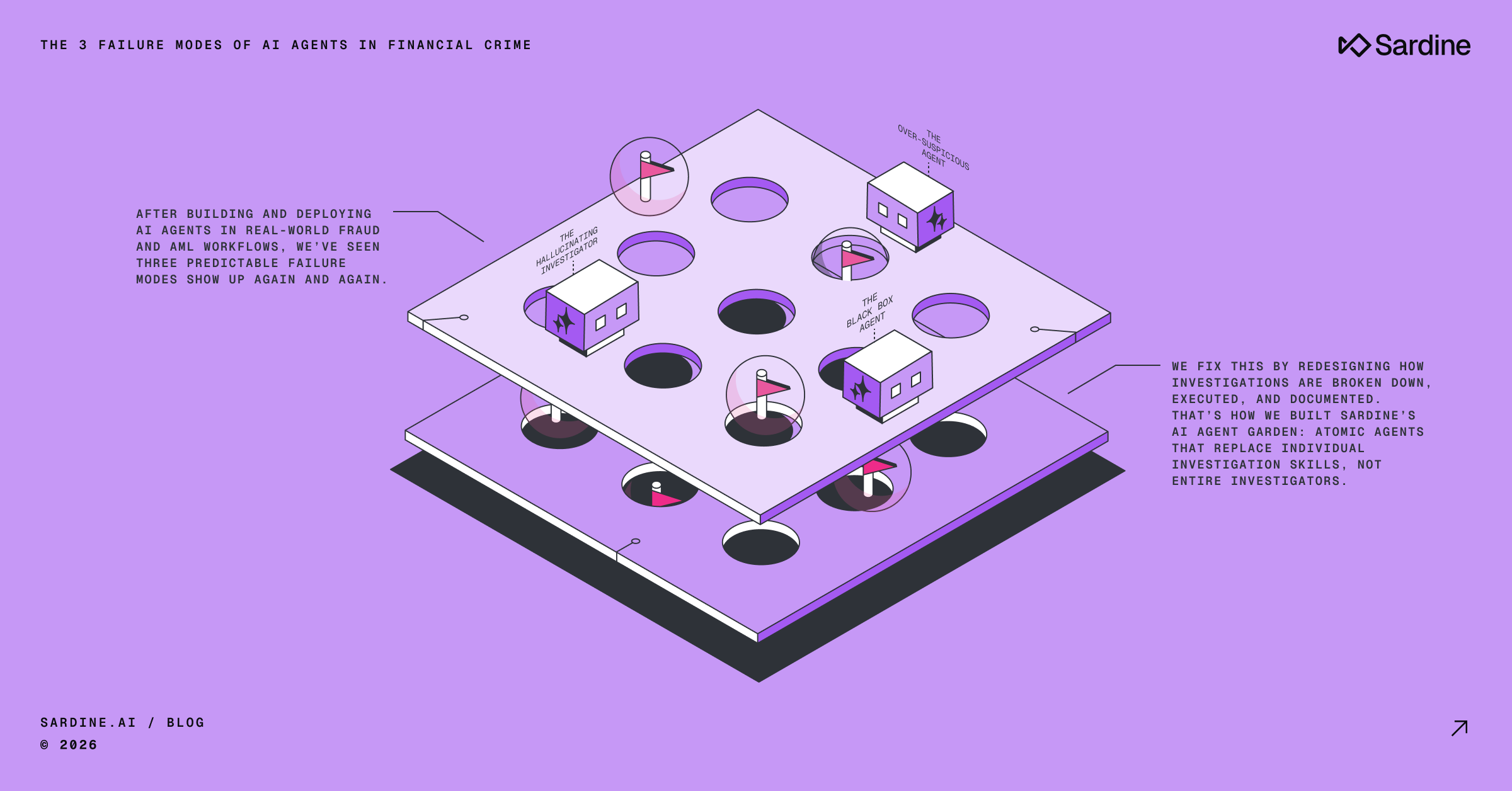

After building and deploying AI agents in real-world fraud and AML workflows, we’ve seen three predictable failure modes show up again and again.

If you’re considering AI agents for fraud, AML, or transaction monitoring, understanding these failure modes is the difference between building a force multiplier and building a liability.

The 3 failure modes of AI Agents

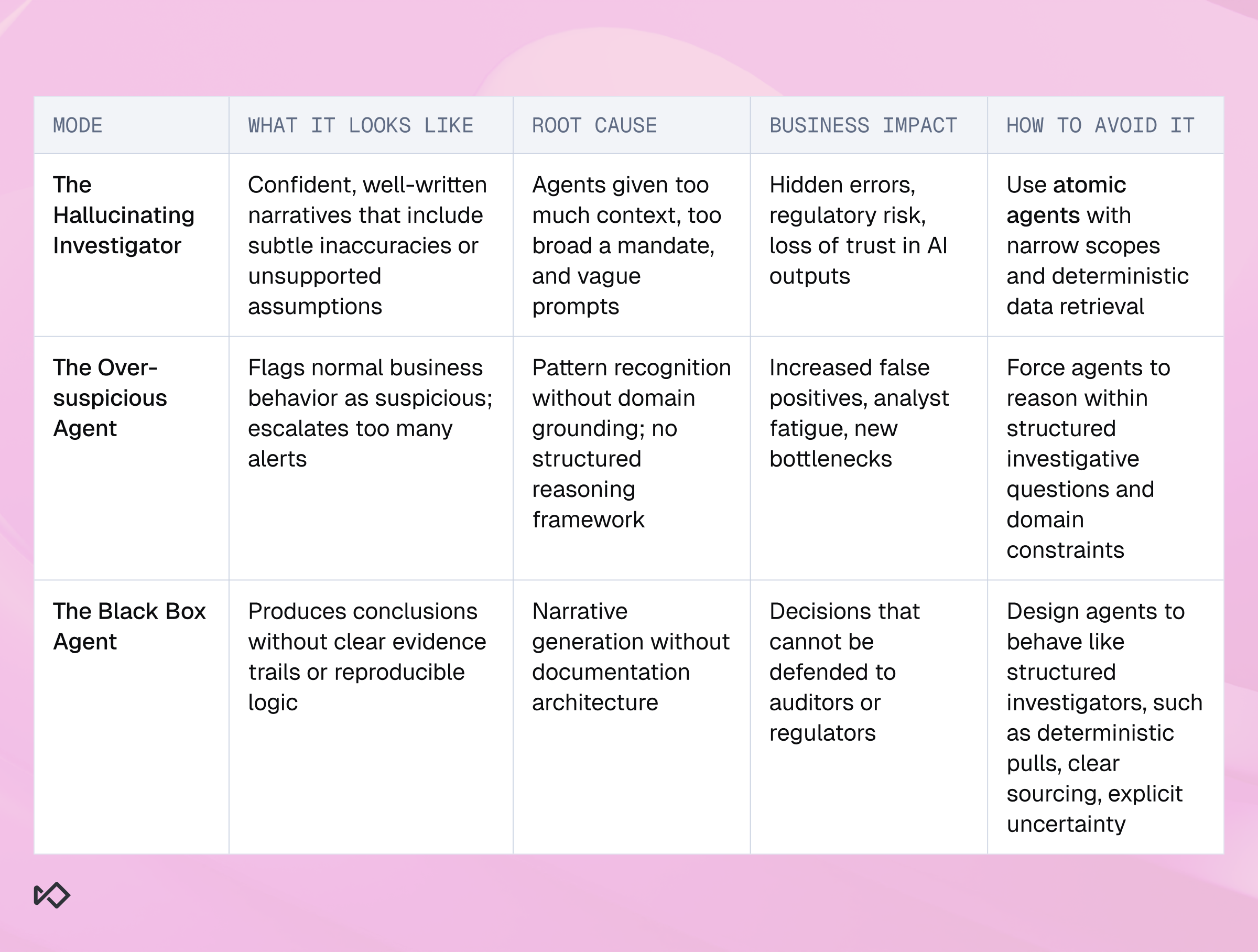

Failure mode #1: The Hallucinating Investigator

The most common mistake teams make is deploying AI agents with too much context and capabilities.

The thinking is understandable: “We have a lot of data. Let’s feed the model everything. It will figure it out.”

In practice, this is the fastest path to hallucination.

The problem isn’t that modern models are incapable. The problem is that fincrime investigations are fundamentally adversarial and evidence-driven, and large, open-ended prompts increase the chance that the model fills gaps with assumptions.

If you ask an agent to “review this customer’s entire profile and determine if this is suspicious,” you’ve given it a task that is too vague, too broad, and too interpretive.

And the model will do what models do best: it will generate a plausible narrative.

Even if that narrative is wrong.

This gets worse by the fact that hallucinations in fraud and AML are often subtle. The agent might infer a business category incorrectly, assume a relationship between two counterparties, or claim that a transaction is unusual when it is completely normal for that industry.

This is why agentic AI in fincrime must be built on a principle that feels almost counterintuitive: Less context often produces more reliable conclusions.

In other words, avoid deploying a “super-agent” that knows everything. Instead, implement a set of narrow agents that each know how to do one thing extremely well.

This is one of the reasons why Sardine is focused on developing what we call “atomic agents”, or AI agents designed around specific investigation primitives. For example:

- A Data Analyst agent that can interpret transactional data

- An OSINT agent that can perform external research and summarize findings

- A KYB agent that can validate business identity and ownership relationships

- A Graph Analyst agent that can interpret entity networks and shared identifiers

The fundamental design philosophy is that agents do not replace humans, but instead replace a specific skill. Since today’s fraud investigations require a variety of skills, and each step in the process demands a dedicated AI agent.

This approach reduces hallucination risk dramatically because each agent operates inside a smaller decision boundary. Instead of “guessing” what matters, it is asked to retrieve, interpret, and summarize specific data in a specific context.

That’s how you build systems that are not just intelligent, but reliable.

Failure mode #2: The Over-Suspicious Agent

The second failure mode is more operational than technical. Even when AI agents don’t hallucinate, they often suffer from a different flaw: they are too quick to assume something is nefarious.

This isn’t because models are “paranoid.” Fraud detection is inherently pattern-driven, and models are trained to recognize signals. But in financial crime, signal recognition without contextual grounding produces a predictable outcome: over-escalation.

The agent sees a high-value payment to a foreign counterparty and flags it.

The agent sees multiple entities connected through shared addresses and assumes it’s a shell network.

The agent sees circular flows and suggests layering.

To a human reviewer, the output sounds intelligent. It uses the right vocabulary and “sounds” like an experienced investigator. But it often misses the most important reality of fincrime operations: most alerts are false positives.

This is where many AI deployments accidentally create a new bottleneck by increasing workloads, not reducing them. Because now your analysts are not just reviewing alerts, they’re reviewing the agent’s reasoning too, which is often overly suspicious.

This failure mode shows up most clearly in transaction monitoring, where a huge percentage of flagged behavior is not criminal at all.

A good example is self-dealing.

Self-dealing is one of the most common patterns that triggers alerts, especially for high-volume businesses. It can look like suspicious circular movement, but in reality it is often just money moving across related accounts, subsidiaries, or internal entities.

To an AI agent trained on “fraud signals,” these can look like suspicious anomalies. To a real investigator, they are normal business operations.

Why does this happen?

We tend to think that training AI on large datasets can teach it all it needs to know. But in reality, true domain expertise is the insights we have on that data. And these insights are by default outside of the dataset.

Tinkering with the dataset or with prompts can only get you so far. To inject real-life domain expertise we need to design agents that are explicitly trained and constrained to ask the right questions:

- Does this counterparty category make sense for this business?

- Is this transaction self-dealing or third party?

- Are the entities connected through ownership, shared identifiers, or operational structure?

- Is this pattern consistent with the industry’s normal flows?

When agents are forced to reason in these frameworks, they become far less likely to “jump to fraud” as the default conclusion.

Failure mode #3: The Black Box Agent

Even if your AI agent avoids hallucination and over-suspicion, it can still fail in the most important way:

It can produce conclusions that are not defensible.

In financial crime, accuracy is not enough. If an agent flags a business as suspicious, a compliance team still has to answer:

- What evidence did the agent use?

- What data sources did it rely on?

- Can the decision be reproduced?

- Would an auditor accept this reasoning?

- Would a regulator accept it?

This is where many AI tools break down.

They output a narrative, but they don’t show the chain of evidence. They cite external information vaguely without clear sourcing. They provide a recommendation without documenting why.

But in regulated environments, AI cannot be a black box. It has to be an evidence machine. A good AI agent should behave less like a chatbot and more like a structured investigator:

- It should pull data deterministically (e.g., from defined queries)

- It should summarize findings in consistent formats

- It should explain why a counterparty is relevant

- It should highlight uncertainty instead of masking it

This changes our definition of what “black box AI” means. It’s no longer about whether I understand the decision or reasoning of a model.

When agents operate inside investigation workflows, such as alert queues, case management, analyst escalation, they need to produce outputs that humans can approve, defend, and audit.

This is why one of the most important agentic capabilities is not reasoning. It’s documentation.

How to deploy AI agents for optimized ROI

If hallucination, over-suspicion, and black-box outputs are the predictable failure modes, then the solution isn’t incremental tuning. It’s structural.

You don’t fix these problems by asking the model to “be more careful.” You fix them by redesigning how investigation work is decomposed, executed, and documented. That’s the foundation behind how we built Sardine’s AI Agent Garden, a set of atomic agents, each one replacing a specific investigation skill, not a whole investigator.

Our goal isn’t to create a single omniscient “fraud brain” that can do everything. Instead, we’re creating a system that behaves like a seasoned investigation team: specialists that do their piece of the work, leave a clean trail, and hand off to the next step.

Let’s look at some examples.

The Data Analyst Agent: “What happened?”

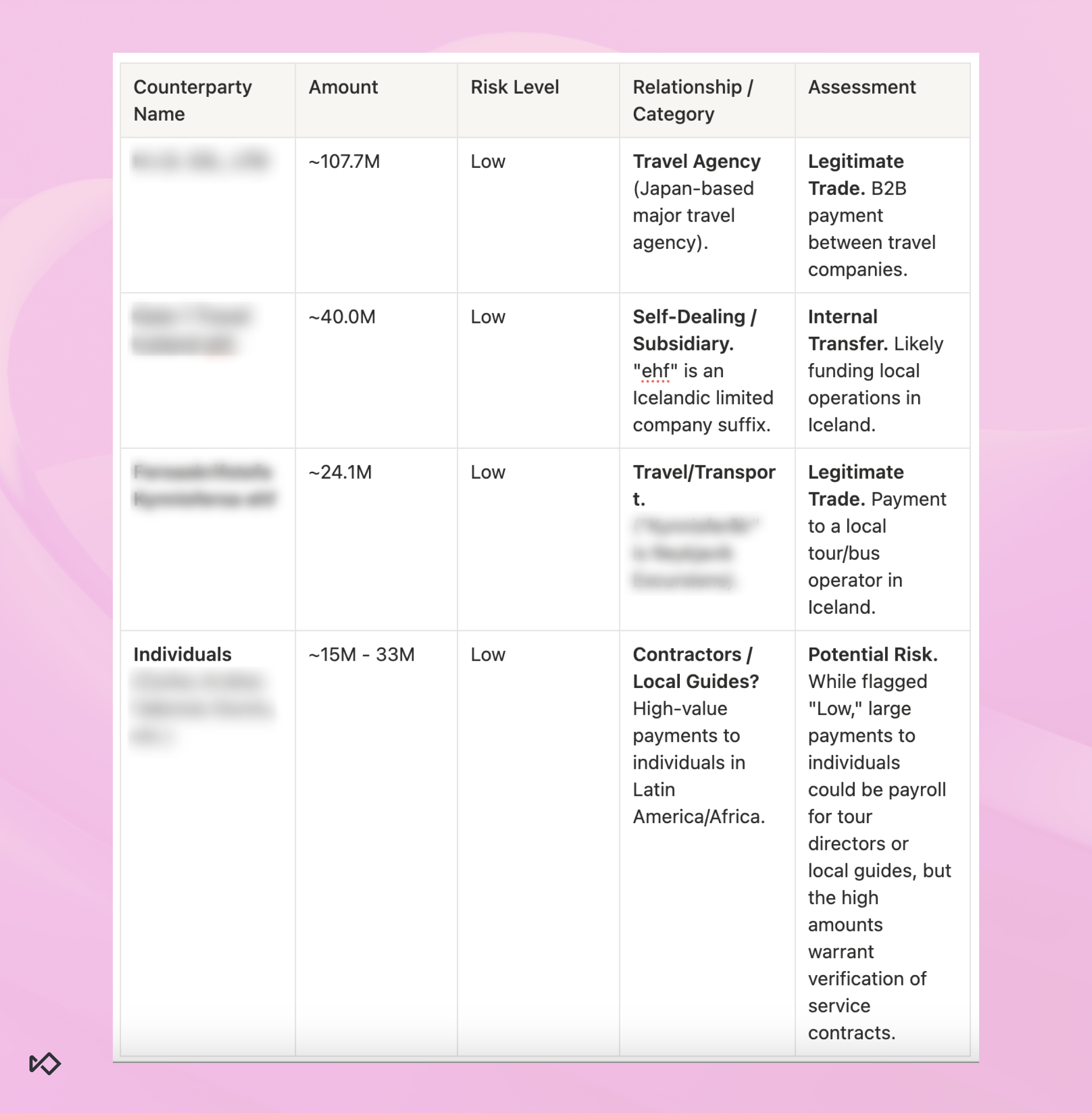

Most investigations start with the same problem: the raw data is unreadable at human speed. Transaction monitoring is the clearest example.

You’re staring at hundreds or thousands of transfers and trying to answer questions that are simple to ask but painful to answer: Who are the top counterparties? What’s the distribution of risk? What’s outward versus inward flow? Is the “weird” behavior a pattern or a one-off?

The Data Analyst Agent is designed to do that first pass, fast. It produces a structured view of activity, including sessions and transactions in the recent time window, ranked counterparties, high-value and high-risk items surfaced first, and context like directionality and timing.

In our Transaction Monitoring setup, that starts from deterministic retrieval, or pulling a defined set of transactions within a defined time range so the agent isn’t improvising what it analyzes.

This is where the most practical value shows up: when the agent compresses data querying and analysis into a single brief that a human can scan and immediately know where to look next.

The OSINT Agent: “What’s the context?”

Once you can see what happened, the next bottleneck is interpretation. Most compliance teams aren’t short on data, they’re short on context. A counterparty name by itself rarely tells you whether a transaction makes sense. And in transaction monitoring, “makes sense” is the whole game.

The OSINT Agent is built for the simplest but most time-consuming task in investigations: turning an entity string into an intelligible business category and a credibility check. Is this a real business? What do they do? Are they plausibly connected to the customer’s line of business? Do they have signals that indicate mismatch, shell behavior, or outright fabrication?

Crucially, this isn’t done for every counterparty. It’s done for the ones that matter: the highest-risk and highest-value counterparties surfaced earlier. That’s how you keep OSINT from becoming an endless rabbit hole (and token sink) and turn it into a repeatable investigative step.

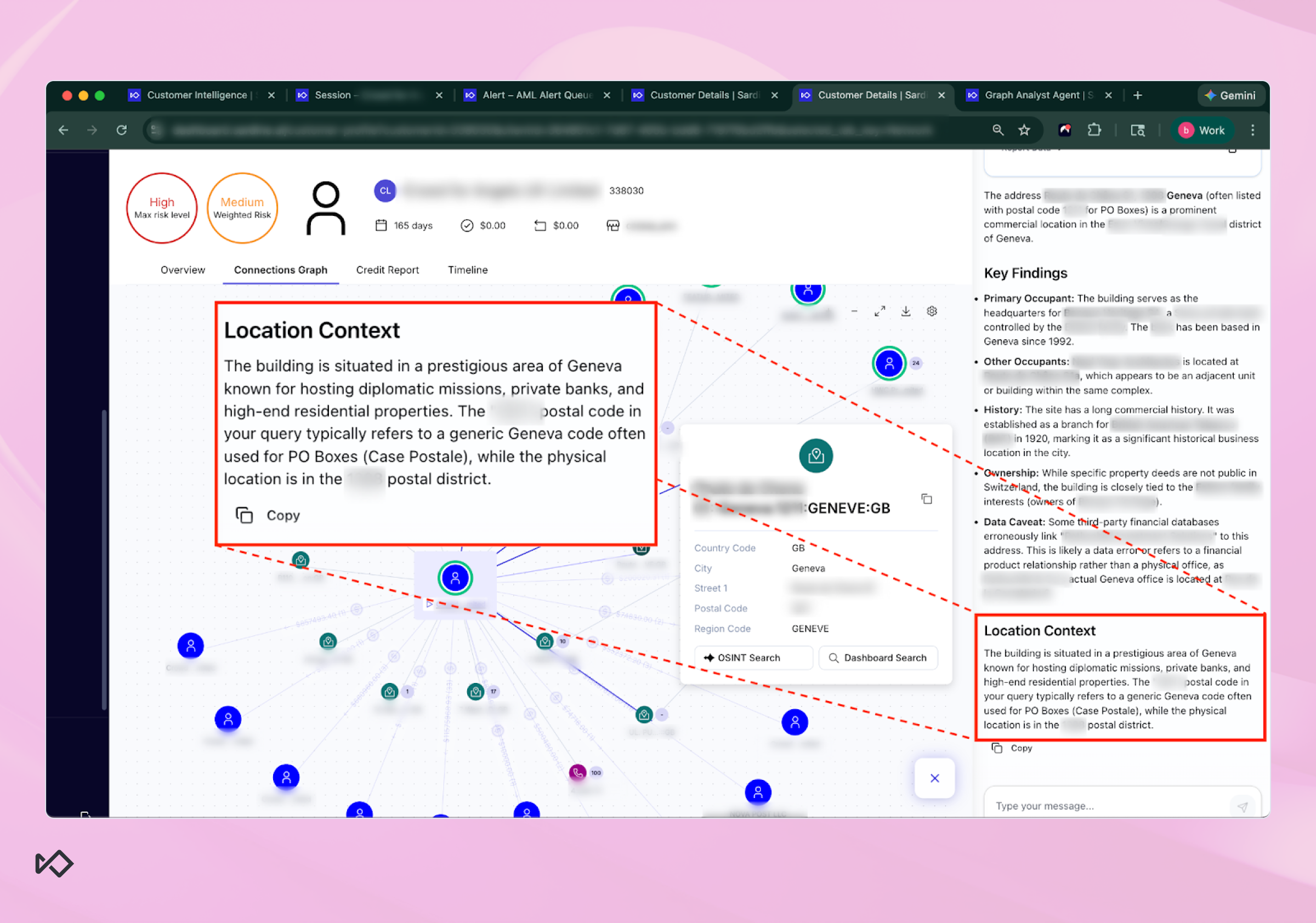

A good example is when a human investigator is looking at a business connection graph and sees a high-risk entity tied to an address in Geneva. On paper, the address looks “legit,” but it could just as easily be a virtual office, a PO box, or a shared services location used by dozens of unrelated businesses.

Instead of forcing an analyst to manually research the address across multiple sources, the OSINT Agent runs directly from the address node in the graph and produces a structured summary of what that location actually represents.

In this case, the agent finds plenty of data that positions the address as an exclusive office building located in a prestigious area of Geneva. But it also highlights the fact that it’s likely being used as a PO Box hub that can potentially harbor illicit activity.

That last point is critical. In fincrime, investigators don’t just need more data, they need to know which data is misleading.

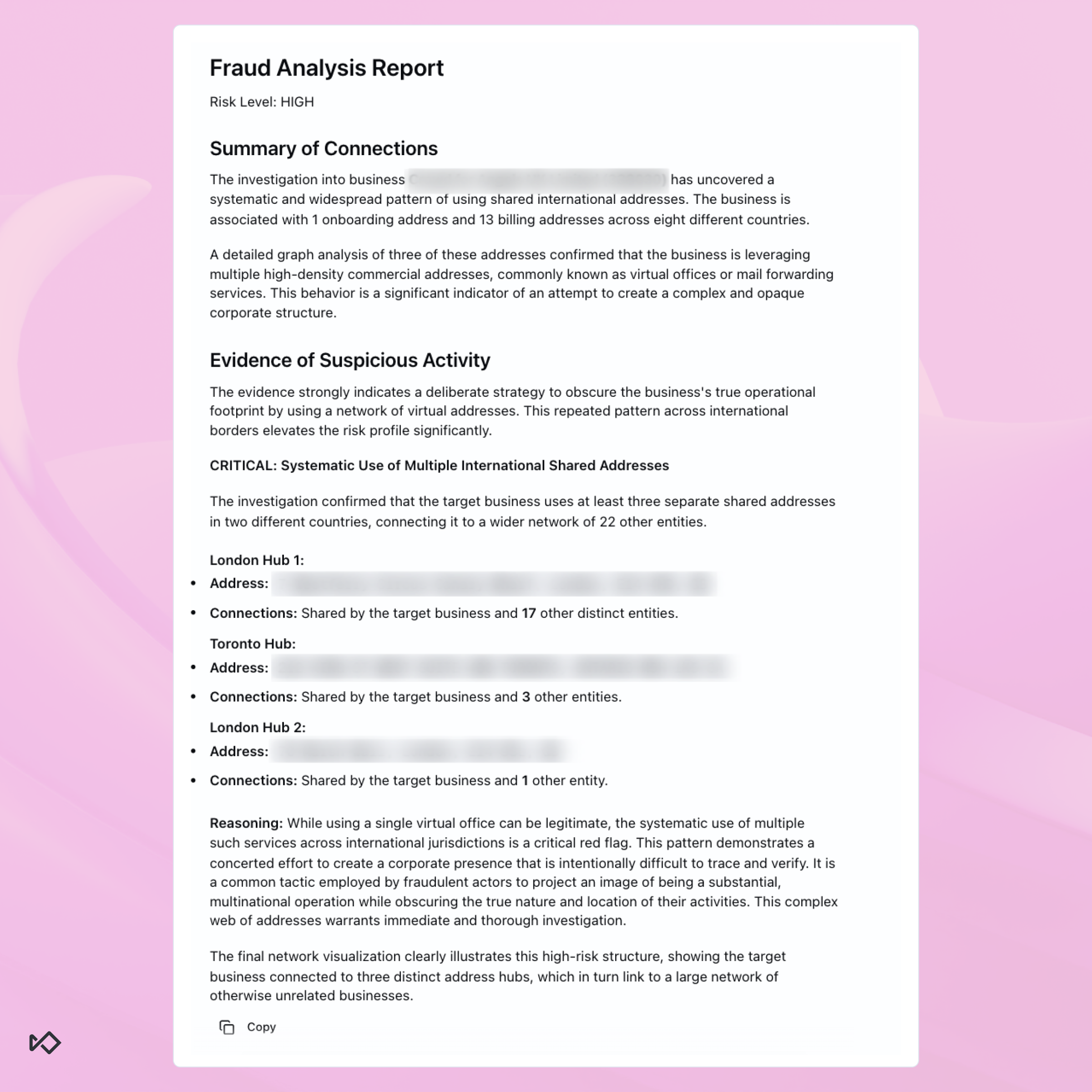

The Graph Analyst Agent: “What’s connected that shouldn’t be?”

If the OSINT Agent tells you what an address is, then the Graph Analyst Agent tells you who else is using it.

In the example above, once the OSINT Agent clarified the Genevan address context and highlighted the possibility of shared usage and data inconsistencies, the next logical question wasn’t “is this address prestigious?” It was: how many other businesses are actually tied to it?

That’s where the Graph Analyst Agent takes over.

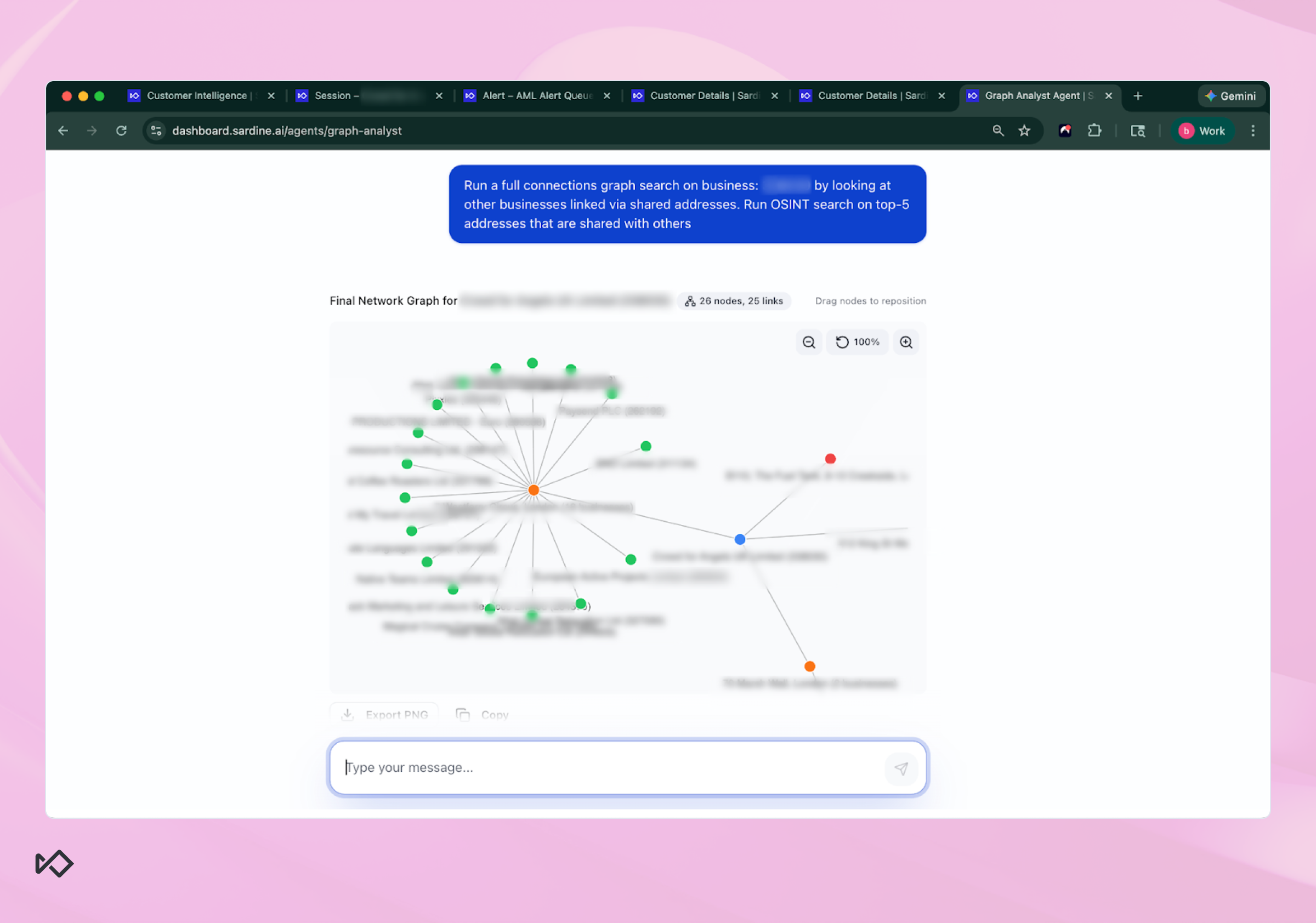

Instead of forcing an investigator to manually investigate all related entities one by one, the agent runs a full Connections Graph search on the business and surfaces every linked entity through shared identifiers.

In the case shown, the graph immediately surfaced multiple businesses connected through shared addresses, including one address that was shared across a large cluster of entities.

What matters here is not the visualization itself. It’s the pattern.

In the screenshot, you can see a central address node with numerous surrounding business nodes linked to it. That kind of clustering can mean very different things depending on context. It could indicate a legitimate multi-tenant commercial building, a shared office provider, or a virtual address used by dozens of unrelated entities.

The Graph Analyst Agent doesn’t rely on intuition. It summarizes the network structure, such as how many nodes, how many links, which identifiers are shared most frequently, and where the densest clusters sit, and then translates that structure into an explicit risk assessment. That allows an investigator to quickly see not only what the agent concluded, but why it concluded it.

This interplay is deliberate. The Graph Agent identifies structural patterns like shared addresses, recurring nodes, and clusters, while the OSINT Agent helps contextualize those high-signal nodes. Together, they transform what would normally be dozens of manual searches into a single coherent view of how a business sits inside its broader network.

That’s the difference between flashy UI and a practical investigation tool.

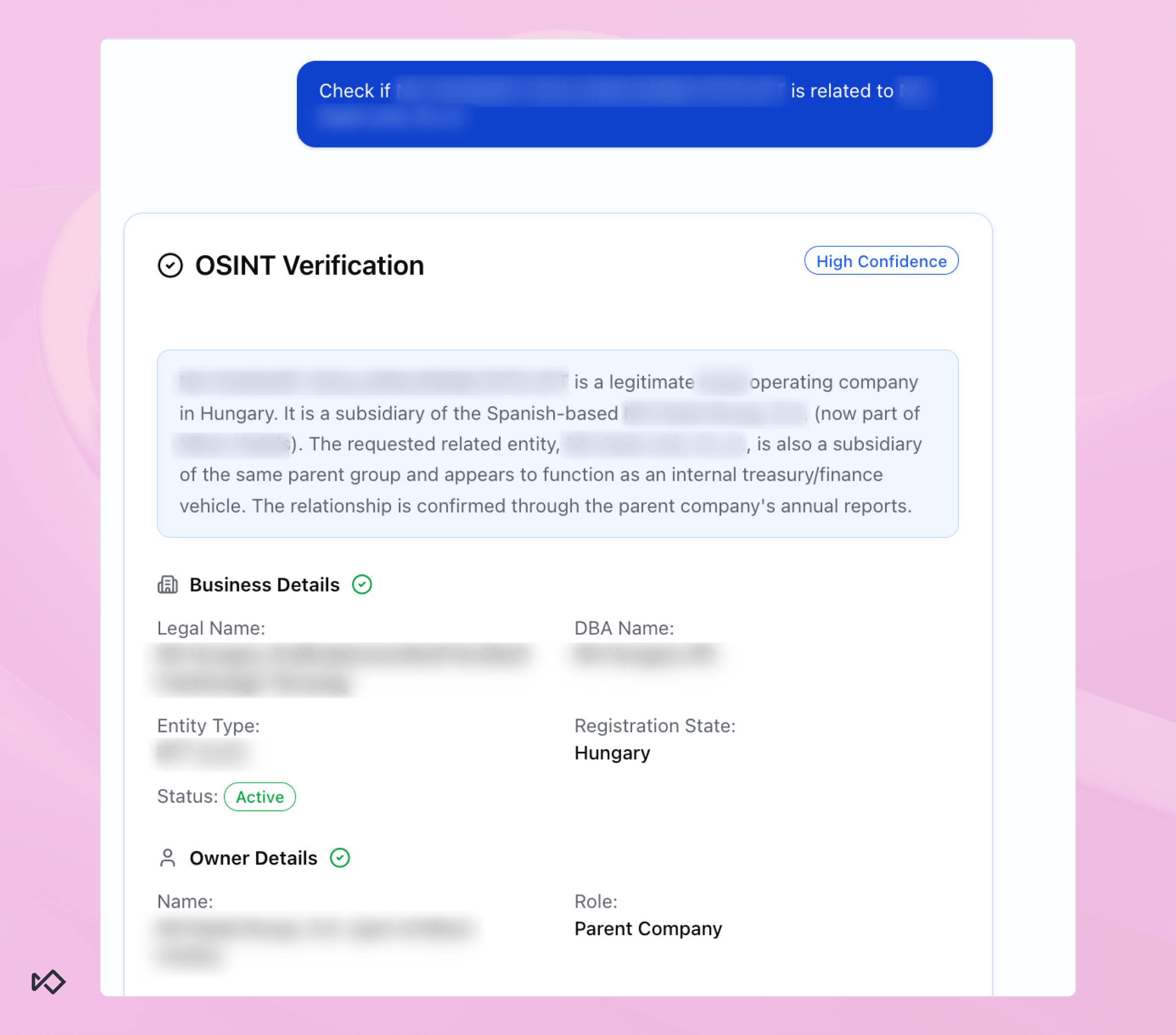

The KYB Agent: “Are these businesses actually related?”

A surprising amount of alert fatigue is caused by one simple limitation: most monitoring systems don’t understand corporate structures.

When a group operates with subsidiaries, internal financing vehicles, treasury entities, shared directors, or brand-adjacent names, the system treats those transactions like third-party risk.

Our KYB Agent is designed to answer a question investigators ask constantly and painfully: are these two businesses actually connected? Knowing the answer to this question can alter the whole investigative process.

For example, an analyst looks at a cross-border transaction between Hungarian and Spanish entities. The KYB agent immediately exposes that the two are subsidiaries of the same parent company. Not only that, but one of them operates as the group’s treasury function, which provides a perfectly legitimate explanation for the transaction.

Chaining and hybrid AI agents

If you stop at individual agents, you end up with an AI toolbelt. Helpful, but not transformational.

The real leverage comes from how we deploy these agents as holistic workflows:

- The Data Analyst agent produces the short list.

- The OSINT agent enriches the list with external data.

- The Graph Analysis agent adds network risk.

- The KYB agent confirms relationships.

- The final output becomes a narrative that can be pasted into a case file.

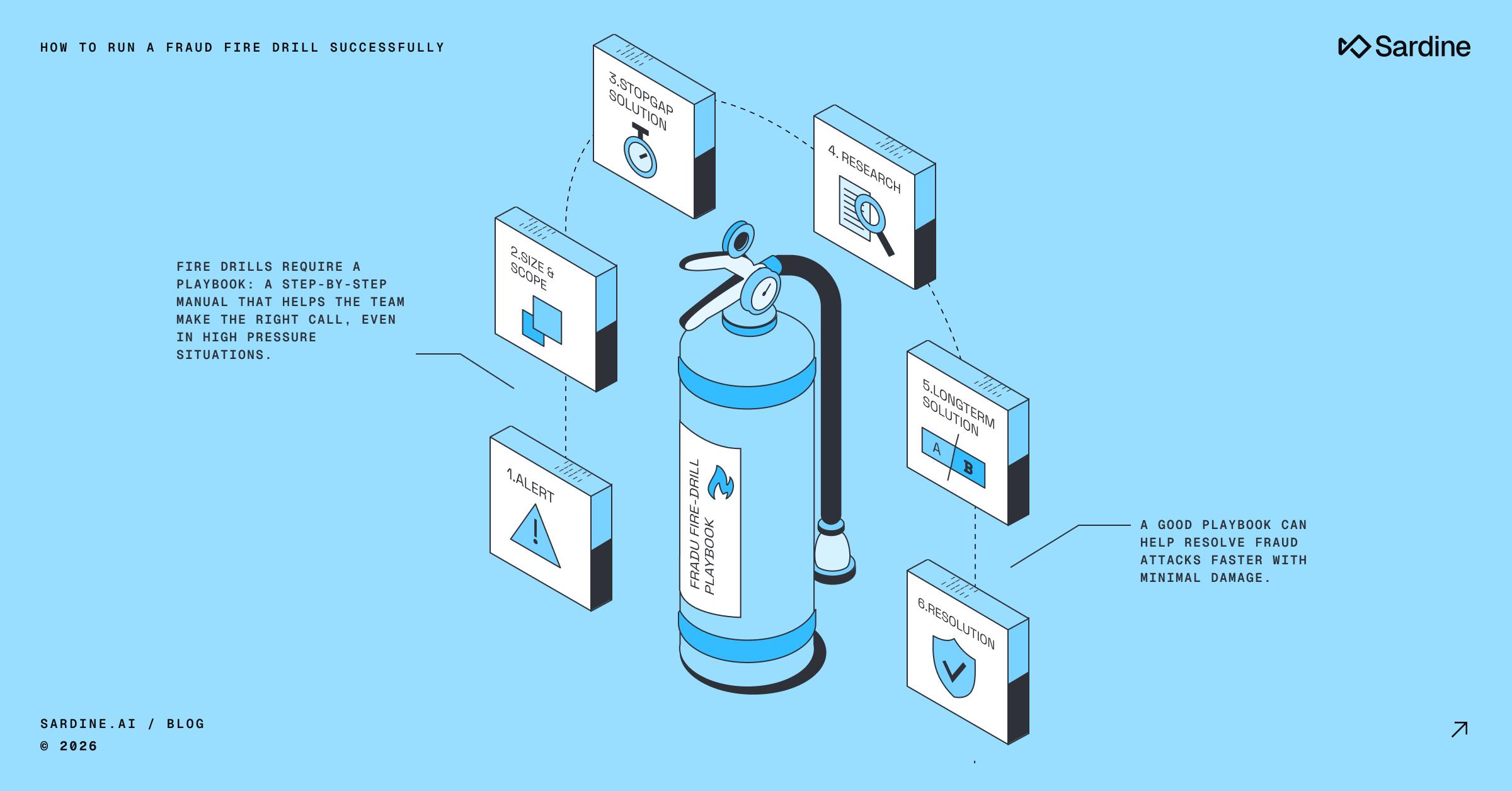

To do that, we’ve designed our AI agents to be deployed around two central principles.

The first one is chaining: being able to link different agents to work sequentially within the same case investigation. It matters for three reasons.

First, it keeps each step narrow and testable. When something goes wrong, you can locate the failure.

Second, it prevents the agent from jumping to conclusions early, because the system is literally designed to gather evidence before it concludes.

And third, it produces documentation as a byproduct, which is the only kind of AI output that survives regulated reality.

The second principle is that each AI agent can be deployed in two different modes: co-pilot or fully autonomous.

Every business has different comfort levels around which activities they are fine with letting AI resolve on its own, and where they would prefer a human in the loop. Resolving high-confidence “green” IDV checks is one thing, but a complex transaction monitoring investigation can be another.

This is also why we made the AI Garden usable in multiple modes: APIs for embedding into existing case management, alert-queue triggers so the right agent runs at the right time, and a standalone chat for ad-hoc investigation.

But the philosophy stays the same regardless of surface area: agents should behave like specialists, and the system should behave like an investigation pipeline.

The real promise of agentic AI in financial crime

Agentic AI is not just a new tool category.

It’s the beginning of a new operating model.

A world where investigation work is no longer limited by human research speed, where evidence is gathered automatically. False positives don’t consume entire teams, and customers aren’t locked out because review queues are overwhelmed.

But that future doesn’t happen automatically. It happens when agents are deployed thoughtfully with guardrails, modularity, and a deep respect for the realities of regulated decision-making.

%20(1).avif)